The Torch Magazine, The Journal and Magazine of the

International Association of Torch Clubs

For 89 Years

A Peer-Reviewed

Quality Controlled

Publication

ISSN Print 0040-9440

ISSN Online 2330-9261

Volume 89, Issue 2

|

Images

of the Deep Anthracite

Miner

by

Richard Aston

Anthracite coal mining was a

major industry in the Wyoming

and Lackawanna Valleys of

North Eastern Pennsylvania

from about 1850 to 1959. Here

I present images of the

miners, who worked up to 2000

feet underground, mostly in

poetry.

The earliest ancestor with our

surname that we know of was

Jack Aston, born in about

1775. He was a coal

miner in Shropshire, England,

as was his son, Richard, my

great-great grandfather, who

was listed in one census as a

grocer, but on his death

record as a miner.

THE ANCESTOR (1)

As a child, during World War

II, I grew up near South

Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, on

Parrish Street, where there

was a coal colliery, and would

watch the miners leaving the

shaft after their shift:

THE VALLEY COAL MINER

Coal was

mined as early as the middle

ages, since the workers of

iron knew that coal produced a

hotter fire than wood, but for

a long time it had only a

small, specialized market.

After the invention of the

steam engine in the late

eighteenth century by James

Watt, and the subsequent

development of the locomotive,

the steam ship, and central

heating in the mid-nineteenth

century, a large market for

coal developed, enabling

deeper mines. As coal

became big business, labor

problems followed. One of the

methods the operators had to

try to keep labor split in

Pennsylvania and weaken the

unions was to bring various

ethnic groups in from all over

Europe. The mule tender in the

following poem tells us about

that, referring to the

immigrant groups with their

slang, usually derogatory,

names:

THE MULE TENDER

That is a folk tale. According

to a plaque at the entrance to

the Anthracite Heritage Museum

in Scranton, Pennsylvania,

over fifty thousand miners

died in the anthracite mines

of Eastern Pennsylvania in the

over one hundred years coal

was king in the region.

One of my great-grand fathers,

Shem Lloyd, worked in the

mines in Pontypridd, Wales and

immigrated to Wilkes-Barre,

Pennsylvania in 1857 to mine

anthracite coal. Shem

Lloyd was a Fire Boss, who, as

part of his job, inspected the

Stanton Mine in our town for

odorless, tasteless, and

explosive methane gas. His

fate is described in this

folk, and family, tale:

THE FIRE BOSS

The coalminer's wives were

busy with gardening, house

keeping and babies; my wife

had three, Mother five,

Grandmother ten, and

Great-grandmother, coal

miner's wife, had seven

survive to adulthood:

THE WIDOW (2)

A coal miner lived next door

to us in a fifteen-foot-wide,

single story house. I would

visit him in his kitchen, the

warm room:

THE OLD MINER

Coal miner's son Ellis

Roberts, a former president of

our local Torch Club, and of

the Wilkes-Barre Business

College, which he owned,

recalls a mine scene:

MINE YARD AT DAWN

The anthracite mines were as

much as two thousand feet

underground in our town, but

near the outcrops of coal

where the valley meets the

mountains, the seams are near

the surface, and the residents

can hear the mine operations,

the jackhammers and blasting,

in their cellars. Some say

they can hear the miners

talking, and Harry Humes, a

coal miner's son and English

professor at Kutztown

University, claims he could

hear them singing while they

worked:

UNDERGROUND SINGING

Some of the miners were

accomplished musicians and

performed for each other.

Gwilym Gwent, called the

Mozart of the Mines, was a

classical composer who would

work out his lines on the coal

cars with chalk. I had the

privilege of singing his

deeply felt choruses with our

local Welsh ethnic Orpheus

Society. Other such

performers included the

juggler of picks:

THE PICK

Anthracite coal production

peaked in 1914, after which

the invention of the internal

combustion engine meant

increased competition with oil

as a fuel for engines and home

heating, causing a steady

decline for coal. The Great

Depression of 1929 took its

toll, leaving miners idle and

deprived of full pay. Business

revived during World War II,

but after it was over, it

declined precipitously as

motor vehicles, diesel engines

on the railroads and in ocean

liners, natural gas for home

heating, and the fact that

bituminous mining is less

labor intensive than

anthracite mining made the

anthracite industry hardly

profitable. Deep mining

in the Northern Pennsylvania

coal field collapsed suddenly

when a local mine tunnel was

run so close to the

Susquehanna River that it

caved; the river flooded

almost all of the mines in

Wyoming Valley, closing them

for good in 1959

Now there are no deep

anthracite miners left there,

except for a few retired men

over eighty years old, nor

traces of the industry that

once dominated the region save

a few colliery buildings,

converted to other uses, and

occasional culm banks covered

with grey birch trees. No

visitor, judging from what

remained visible, would know

that for more than a century

"Coal was King" in our region.

The last of the coal breakers

in the Northern Coal Field was

demolished at the Huber

Colliery in the Spring of

2014:

REMEMBERING THE HUBER (3) If the deep miners are extinct in our valley, they live in us their descendants, this one biking over the hills of the former coal towns: BIKING HILLS (4) Footnotes

(1)

This poem, along with "Valley Miner,"

"Mule Tender," and "Fire Boss,"

appears in Valley Voices.

(2) This poem appeared in Endless Mountain Review. (3) This poem first appeared in the Wilkes-Barre Citizens' Voice of May 12, 2014. (4) This poem first appeared in Mulberry Poets and Writers Association Day Book. Works Cited

Aston,

Richard. Valley

Voices. Kanona, New

York: Foothills Publishing,

2012.

_____. "Leaving the Mines." Endless Mountain Review 1.1 (February 1988), 8. _____. "Remembering the Huber.” Wilkes-Barre, PA Citizens' Voice, May 12, 2014. _____. "Biking Hills." In Mulberry Poets and Writers Association Day Book. Scranton, PA: Mulberry Poets Writers Association, 1998. Humes, Harry. Underground Singing. Lewisburg, PA: Seven Kitchens Press , 2007. Roberts, Ellis. Along the Susquehanna. Wilkes-Barre, PA: Bardic Books, 1980. Author's

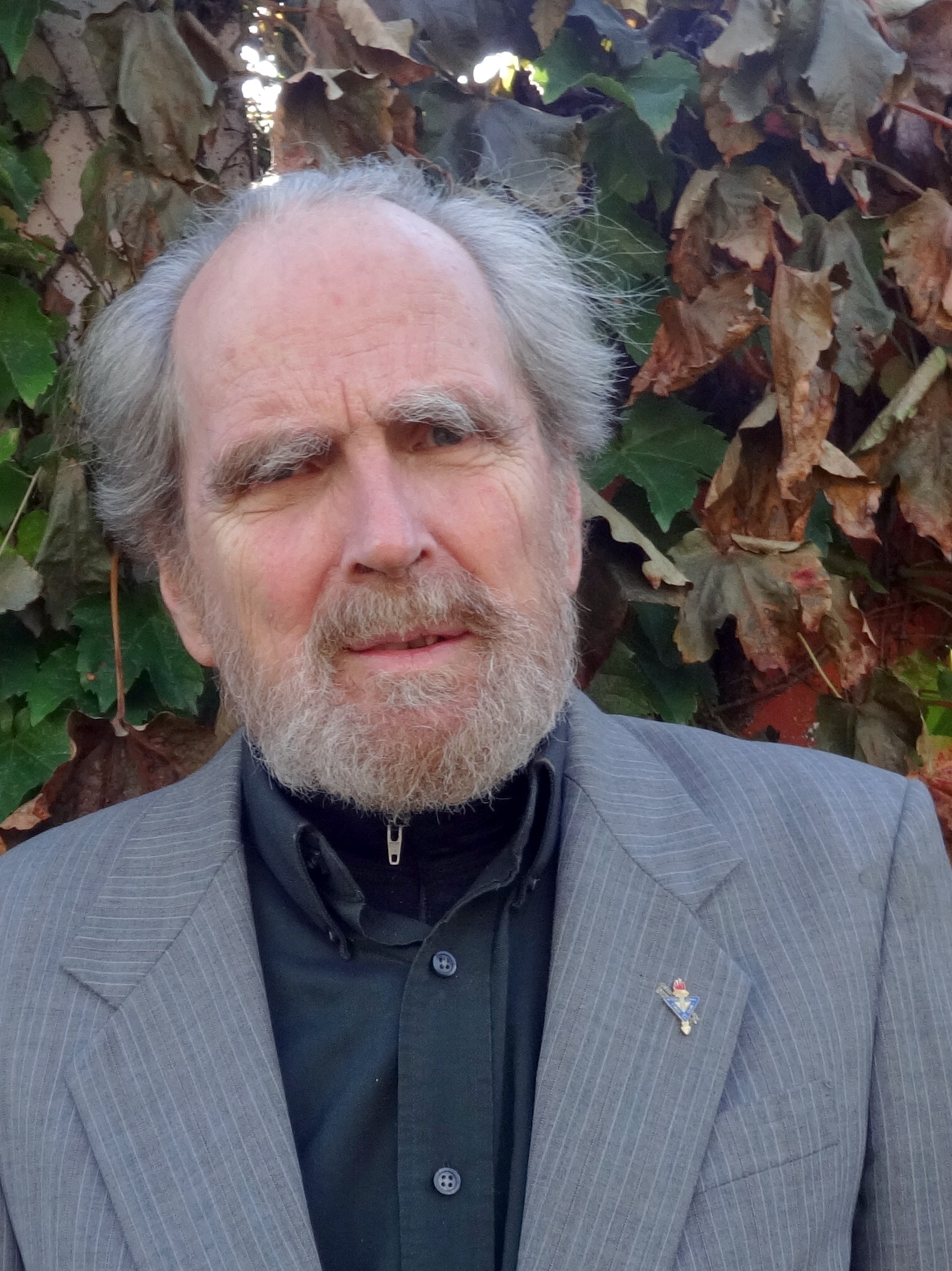

Biography

Richard Aston graduated from

Ohio State University with a

Ph.D. in engineering in 1969,

worked in aerospace engineering

for several years, and taught

engineering and engineering

technology for 27 years. He is

the author of three engineering

textbooks from commercial

publishers and of one available

free on the Internet. He

has also published four previous

papers in The Torch.

He has been publishing poetry and criticism for over 35 years. His poetry collection Valley Voices was published by Foothills Publishing in 2012. He and his wife, Marcia, have three grown children and seven grand children. His paper was presented to the Wyoming Valley Torch Club on September 8, 2014, in a dark room lit only by a miner's helmet light. ©2016 by the

International Association of Torch

Clubs An EBSCO Publication

|