The Torch Magazine, The Journal and Magazine of the

International Association of Torch Clubs

For 89 Years

A Peer-Reviewed

Quality Controlled

Publication

ISSN Print 0040-9440

ISSN Online 2330-9261

Volume 89, Issue 2

|

Connecting

the Dots between Species

Extinction,

Overpopulation, and the

Use of Resources

by

Marshall Marcus

Species extinction is not

new. Since childhood we

have heard about the

disappearances of wooly

mammoths, saber-tooth tigers,

Neanderthal man, and passenger

pigeons. Now emerging,

however, is information that

world-wide mass species

extinction is happening,

accelerated by the Industrial

Revolution. Once these

species are extinct, it will

take millions of years of

evolution for replacements to

appear. Extinction is

happening at an exponential

rate, a rate that in another

century may result in

destruction of the biological

diversity adequate to support

us.

Biological diversity gives us

the raw materials for our

economies, provides us our

food, recycles our waste,

prevents erosion, and protects

us from solar radiation.

Losing that diversity will

reduce the earth's carrying

capacity to support Homo

sapiens. Exceeding

carrying capacity will mean a

massive die-off of

humans. There is clear

evidence that the main driving

forces behind loss of

biological diversity are world

overpopulation and the

wasteful use of resources

required to support

overpopulation.

The total number of species on

earth may be between 10 and 30

million. The natural or

"background" loss of species

is somewhere between 0.1 and

one species per million per

year, depending on whose

research is being cited.

Assuming there are ten million

species and not counting

unclassified species, a normal

extinction level is between 1

and 10 species lost per

year. But, since about

1900 we have become aware that

during a period of time

measured not in millions of

years but in decades, many

more than ten species per year

have become extinct or are

facing extinction.

The terms

"threatened" and "endangered,"

as defined in the U.S.

Endangered Species Act of

1973, help in understanding

the process of

extinction. Threatened

means a species is still

abundant but, because of

declining numbers, is likely

to become endangered in the

near future. Endangered

means a species is in

danger of extinction in all or

a significant part of its

range. The Red List

of the International Union for

Conservation of Nature (IUCN),

headquartered in London, lists

thousands of currently

threatened, endangered, and

extinct species. Examples of

the latter in the U.S. include

the Ivory Billed Woodpecker,

the Carolina Parakeet, and the

Eskimo Curlew, millions of

which used to fly along the

west coast, wintering in the

Arctic and flying to South

America for the summer.

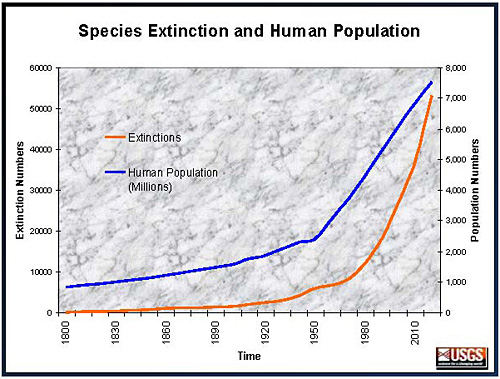

The beautiful Monarch butterfly, now a threatened species, is a case in point. The fall migrations of the Monarchs take them to nesting sites along the west coast of North America and into Mexico. After steep and steady declines in their numbers at nesting sites in Mexico for the three years prior to 2013, that year found these black-and-orange butterflies covering only 1.6 acres, compared to 2.9 acres in 2012. They covered more than 44.5 acres at their recorded peak in 1996. Major contributors to their decline are believed to be loss of habitat and a decrease in milkweed growth in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. The loss of milkweed, a primary source of food for the Monarch, may be the result of the widespread use of Roundup, a Monsanto herbicide sprayed on genetically modified wheat, corn, and soybean crops in the U.S. Most extinctions result from loss of habitat as human population has increased; other causes include hunting for profit and food. Decimation in Africa of rhino and elephant herds for body parts is well known, as is killing for "bush meat," such as killing tapirs for food in South America. Species extinction is also being driven by the importation of invasive species, such as the Argentine Tegu lizard introduced into Florida. Introduction of massive amounts of pesticides and herbicides into the world environment, as in the example of the Monarch butterfly, is another driver. Far northern habitats are being lost as more heat from the sun is absorbed by the open Arctic sea, instead of being reflected back into space by snow-covered ice. Extra energy absorbed is so great that it measures about one-quarter of the heat-trapping effect of atmospheric carbon dioxide (Cory). Devastation of habitats by oil extraction and strip mining of coal and tar sands is well known. Examples in North America range from the waste ponds of the Canadian tar sands, to BP's 2010 catastrophe along the Gulf Coast, to the 1.1 million gallon oil spill in 2012 along the Kalamazoo River in Michigan. The same devastation occurs in the mining of copper, gold and other minerals. The problem is not caused by the number of Homo sapiens on earth alone; our habits of consumption and waste generation add to it. Our waste products pollute the ground, the oceans, the aquifers and rivers from which we draw our drinking water and the air we breathe. Among the causes of the die-off of corals in the oceans, for instance, is the extinction of ocean-dwelling species by air pollution from carbon dioxide. Airborne carbon dioxide reacts with dissolved carbonate ion (CO3−2) in seawater to form bicarbonate ion, HCO3−1. This removes carbonate from seawater, and carbonate is the building block of many crustaceans and corals. Removing carbonate from seawater slows the process of calcification and threatens the survival of a multitude of aquatic species. This reduction of available carbonate is not the only outcome; in the process the oceans become more acidic. Normally seawater is slightly alkaline on the pH scale, at pH = 8.1, where pH = 7 is neutral (neither acidic nor alkaline). A recent study concludes that at atmospheric carbon dioxide levels of 500 to 650 parts per million (ppm), negative effects of increased ocean acidity outweigh positive ones for corals, mollusks and fish, but not for crustaceans (Wittmann and Poertner). Above that level, all sea creatures are harmed. At 650 ppm of atmospheric CO2, ocean acidity will drop to a pH of approximately 7.8. That is about where corals stop growing. Most other ocean species that use carbonate will also slow or cease their uptake of carbonate. They then begin an accelerated die-off. How close are we to 650 ppm? We are now approaching a world-wide level of 400 ppm. Data from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration show that between 1959 and 1999, atmospheric CO2 increased 1.3 ppm/year (Tans). Between 1999 and 2014, CO2 increased 2.0 ppm/year. This could be an indicator that not only the increase itself, but the rate of increase is also becoming exponential. As the rate of increase in atmospheric CO2 becomes exponential, it may easily average more than 3.0 ppm per year in the next 80-90 years, causing atmospheric levels to exceed 650 ppm. Scientists already have enough preliminary data to show the connection between the world-wide increase in human population and species extinction. The data have been available for years, but have not been widely publicized. Extinction is being faced by every species in the taxonomic system of classification, including us in the long term. In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey's Idaho Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Service Research Unit at the University Of Idaho published the attached graph summarizing what was known then about species die-off (Scott). The graph shows two curves, the top one reflecting population in billions of Homo sapiens and the bottom one the estimated species extinctions in thousands worldwide. Both curves rise slowly until the Industrial Revolution and then shoot up exponentially as the earth's human population approaches seven billion by 2010.

Assuming a

base of ten million species,

and leaving out unclassified

bacteria and Archaea

species, results like these

indicate that in the 100 years

from 1810 to 1910, the world

lost possibly 1,200 species,

about one per million,

equivalent to perhaps ten per

year. Between 1910 and

2010, the projected loss

worldwide was 32,000 species,

most of that occurring between

1980 and 2010, as species

losses became

exponential. From these

earlier data, some researchers

put the loss rate after 2008

at about 2,500 times

pre-Industrial Revolution

background (Myers).

Researchers with more recent

data put the background

species extinction rate

somewhat lower, at about 1,000

times the pre-Industrial

Revolution rate (Pimm,

Jenkins). In either case, huge

numbers of species are

disappearing. Once gone,

they are gone forever. We can

only assume a proportional

loss of unclassified species,

ones that will never be known

to science. Only millions of

years of future evolution can

replace lost species.

Many will ask: Aren't some extinctions part of the natural order of things? Haven't there been extinctions before? Yes, starting with the Ordovician extinction 440 million years ago, there have been at least five major previous mass extinctions. Paleontologists have clues in the geologic record as to causes. The Ordovician mass extinction, for example, appears to have been caused by glaciation. At that time most life was in the sea, and some 85% of all sea life perished. Even more extensive was the Permian extinction 251 million years ago, also probably due to glaciation, in which perhaps 96% of species disappeared. All life now on earth has descended from the remaining 4%. However, no evidence exits that any of the five major extinctions was caused by the activity of one species, as is the case now. Science journalist Elizabeth Kolbert's The Sixth Extinction, which mirrors the ideas of Harvard paleontologist Niles Eldridge, author of a 2001article of the same title, describes how a sixth mass extinction began to accelerate with the Industrial Revolution. Her excellent book describes the symptoms of the current extinction but does not explore in detail the main underlying cause, namely world overpopulation and how to deal with it. *

* *

Demographers, those who

analyze population data,

provide clues as to the

outcome of steadily growing

populations. One famous

demographer, Thomas Malthus

(1766-1834), argued that since

populations increase

geometrically while food and

living space do not, life can

be made tolerable only if

births are limited, or by

death and violence. The

Malthusian operators of death

and violence aren't working in

the 21st century to decrease

overpopulation. So, why

not apply his other solution

and limit births?

There are pros and cons about limiting births. If you run a business that makes more profit as you sell to more people, exponential population growth may appear to be attractive, as may the prospect of bringing in new, young converts if you support a particular religion or ideology, as the population expands. Some suggest that exponential population growth may even be beneficial. The argument goes like this: increased population will create pressure for entrepreneurial innovation; that will result in new technologies (e.g., fracking and genetically modified foods); those will allow a further increase in population; that, in turn will result in more innovation; and the cycle will repeat. Is that a good argument for increasing world population? You can draw your own conclusion. Leave profit-taking, religion and ideology out of the discussion for a moment, and answer the following question: What advantage does more than doubling the population of the world from 3 billion in 1960 to over 7 billion in 2014 offer to the hope for avoiding depletion of resources, improving the quality of human life world-wide and protecting the planet's biodiversity? For the vast proportion of people on the planet, there appear to be no long-term advantages from an increasing population. To the contrary: the disadvantages far outweigh any supposed advantages. For example, overpopulation has created a surge in uneducated and unskilled workers subject to a chronic disadvantage with respect to jobs that pay a living wage. Aware of this and other problems created by overpopulation, some countries have made efforts to control population growth or make family planning a requirement for couples prior to marriage. China is an example of the former and Iran an example of the latter. Meanwhile, worldwide exponential human population growth continues with the world probably already well past its sustainable carrying capacity for humans. The problem facing us is how to slow and reverse the 200-year trend of overpopulation and its consequence of mass species extinction. Can democracies survive overpopulation and lead the way to saving species like the Monarch butterfly? Science writer Isaac Asimov, for one, was skeptical, once telling an interviewer, "Democracy cannot survive over-population. Human dignity cannot survive it. Convenience and decency cannot survive it. As you put more and more people into the world, the value of life not only declines, it disappears. It doesn't matter if someone dies. The more people there are, the less one individual matters." Some cite the example of India, where increased education and a slowing birthrate, together with increased crop yields and an emerging middle class, all create optimism about the ability of the country to survive and prosper. Unfortunately, that example will fail as India's biodiversity is destroyed. A growing middle class is the tip-off: with the upward economic mobility of millions of Indians, there will be the accompanying growth of consumption. That means the loss of habitat to provide housing and food; the loss of more habitats will mean the destruction of more species. There is a direct route to slowing population growth, but in many countries it is a very difficult route to establish. That route involves the four common methods used to control overpopulation around the world: contraceptives, abortion, voluntary tubal ligation, and voluntary vasectomy. All are remarkably effective but not equally desirable. Most common is the use of contraceptives, believed to be largely responsible for the drop in abortions in the U.S. and elsewhere. Globally, as women have become empowered and sex education more available, the methods mentioned to avoid abortion have become widespread. It will be necessary to involve the world's religions and ideologies as part of the solution, admittedly a difficult task. Perhaps we could start by agreeing on the sources of objective information and accepting historical facts behind the impact of human overpopulation and excess consumption on the world's biodiversity. For example, scientists have established that the earth is 4.5 billion years old and that human beings originated some 6 million years ago (Dawkins). However, a Gallup poll in 2012 found that 46% of Americans believed that God created life on Earth within the last 10,000 years. I disagree, but for the sake consensus we could let that difference go, if the same folks who believe in a more recent origin of the planet would agree that God also created some ten million plus species 10,000 years ago, and that they are now dying off at maybe 30,000 per year. With that basis, it may be possible for religions and ideologies to reach a consensus that overpopulation is the main reason for species die-off, and agree on what needs to be done to reach a sustainable level of population and heal the planetary devastation we have created. It may require decades and perhaps Malthusian operators, the equivalent of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—conquest, war, famine and death—to nudge religious and business leaders to seek population stabilization, and then a reduction below our present seven billions of Homo sapiens. *

* *

What plan,

what paradigm, will give us

some hope of slowing species

extinction and loss of

biodiversity? The simple

answer is that we need a

cultural change to something

else, away from the culture of

exponential population growth

against a background of

shrinking resources, away from

a worldwide culture that

equates GDP growth with

success. If we in the

U.S. take as a priority

slowing and then stopping mass

species extinction here and

world-wide, and accept that

our increasing populations and

habits of consumption are the

main sources of the problem,

then the U.S. as a nation has

a marvelous opportunity before

it.

What can you and I do about the situation? We can let our concern about species extinction be known to our state and Federal elected representatives; we can push for our school boards to require that the history of species extinction be taught from elementary school on; and we can join a group that provides the public with educational materials on species extinction. Examples of such groups are the Center for Biological Diversity, the Nature Conservancy, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and the World Wildlife Fund. I urge you do what you can to prevent the destruction of the world's biodiversity and prevent the Malthusian operators of violence and death becoming dominant in the world. Works

Cited

Asimov,

Isaac. Interview by Bill Moyers.

Bill Moyers' World Of Ideas

(17 October 1988).Cory, Rose, et al. "Surface exposure to sunlight stimulates CO2 release from permafrost soil carbon in the Arctic." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110.9 (February 17, 2014), 3429-3434. Dawkins, Richard. The Ancestor's Tale. Houghton Mifflin, 2005 Eldridge, Niles. "The Sixth Extinction." ActionBioscience.org, June, 2001. Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction, an Unnatural History. Henry Holt, 2014. Myers, Norman. "Biodiversity and the Precautionary Principle." Ambio 22.2-3 (May 1993), 74-79. Pimm, S.L., Jenkins, C.L., et al. "The Biodiversity of Species and Their Rate of Extinction, Distribution and Protection." Science 344 (May 30, 2014). Scott, J.M. Threats to Biological Diversity: Global, Continental, Local. U.S. Geological Survey's Idaho Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Service Research Unit at the University of Idaho, 2008. Tans, Pieter. "Trends in Atmospheric Carboin Dioxide." Website of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration/ Environmental Remote Sensing Laboratory (NOAA/ERSL), March, 2014. Wittmann, Astrid, and Poertner, Hans-Otto. "Sensitivities of extant animal taxa to ocean acidification." Nature Climate Change 3.11 (January 2013), 995-1001. Author's

Biography

A native of Memphis,

Tennessee, Marshall Marcus

earned a B.S. in chemistry at

Memphis State College

following two years of oil

exploration in Brazil, and

afterwards an M.S. in

chemistry from the University

of Kentucky.

After teaching chemistry at Transylvania College in Lexington, Kentucky, he worked as a polymer research chemist, first with DuPont and then with Firestone. His interest in industrial hygiene led to employment by the State of Virginia as a state OSHA supervisor. After being awarded national certification as a Certified Industrial Hygienist, he worked for 29 years as a safety and health consultant for corporations, school districts and the federal government, retiring in 2010. He has been an ardent Appalachian Trail hiker; choir member and vestryman in the Episcopal Church; Red Cross chapter director; and Red Cross volunteer near New Orleans following hurricanes Katrina and Rita. He is married and has one daughter. He and his wife Virginia live in Richmond, Virginia. His paper was presented at the Richmond Torch Club on April 1, 2014. ©2016 by the

International Association of Torch

Clubs An EBSCO Publication

|