The Torch Magazine, The Journal and Magazine of the

International Association of Torch Clubs

For 91 Years

A Peer-Reviewed

Quality Controlled

Publication

ISSN Print 0040-9440

ISSN Online 2330-9261

Volume 90, Issue 2

|

By

the Numbers

by R. Paul Moore

Golf

is a lot like taxes, according to the

old joke. You drive hard to get to the

green and then end up in the hole.

Every year around April 15, Americans have a rendezvous with debt. To better understand how our governments taxes us, what the money is spent on, and how these things have changed over time, this paper will take a non-political look at reasonably good descriptive statistical information, by the numbers. We hear a lot about spending, taxes, the national debt, the deficit, etc. How meaningful is it to the average person? How much does the government spend and where does the money come from? How have these things changed over time? What does the future hold? What is my fair share? To begin, consider the following two familiar assertions:

The second statement is somewhat more difficult to prove or disprove. One might suspect that the underlying sentiment is "some other folks are not paying enough, but I am paying too much." To think about taxes and spending in this country, we must consider some very large numbers. We know one million is a one with six zeros following, a billion has nine zeroes, and a trillion has twelve. But often when we hear how many dollars were spent on some project, we want to say "Wait a minute, was that millions, billions or what?" How much is a billion dollars on a per person basis? With about 320 million people in the US, a billion dollars is roughly $3.12 per person, which seems like very little. When congress voted a third of a billion in 2005 for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, was it worth it? Was it worth about $1 from each person in the country? That question is difficult to answer. As the total number of projects increases, the amount spent in billions and trillions of dollars adds up. As Senator Everett Dirksen famously said, "A billion here, a billion there, and soon we're talking about real money." But I will try to make sense of it, by the numbers. *

* *

First, consider what the government

takes in and spends. By the

numbers, how much of the tax money

comes from the various sources?

Table 1 shows the breakdown of tax

revenue from income taxes, social

insurance, ad valorem taxes, fees and

charges, and business/other

revenues. The table

includes estimated or actual data for

all types of taxes collected from all

three sources—federal, state and

local—in Fiscal Year (FY) 2015.

The federal information in Table 1 is based on the President's budget for FY 2015. The President's budget serves as a blueprint for the appropriation bills but is not binding and often is not approved by Congress. The complex process leading to the appropriation of funds involves at least twelve committees in each branch of Congress. Moneys are first authorized and later appropriated by these committees. The state and local numbers in Table 1 are combinations of actual known and estimated amounts. Table 1 (from

Chantrill website)

In total, a little

more than half of the six trillion

dollars in direct revenue is accounted

for by federal taxes, with the

remainder split between state and

local taxes. Surprising as it

may seem, only about half of the total

tax revenue this year will be

collected by the federal government.

Table 1 also shows the breakdown of the six trillion dollar total revenue by the three levels of government and by type of tax. Over half, about 57%, of the more than three trillion dollars in federal tax money comes from income tax. About one third of the federal taxes come from social insurance taxes (that's Social Security, Medicare, and the like). On a per person basis, the total federal taxes are $9,925 per person, and the total from all levels of taxation is $18,700 per person. That "Business and Other Revenues" at the federal level accounted for only about 3% of the federal revenue seemed small, so I looked up some information about corporate taxes. Corporate income is generally taxed at a 35% rate, and that rate receives a lot of attention. However, the effective corporate tax rate is much lower. The Congressional Research Service reports that corporate taxes were 6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1952 but have declined to 2% in 2011 and were between 1 and 3 percent during all of the years from 1983 to 2009. These lower effective tax rates are due to deductions, exemptions, and tax credits received by corporations. Also, there have been significant increases in the amount of business income taxed through the individual income tax. Over 50% of business income is now taxed as individual income since it is passed through to individuals from partnerships and S corporations. Table 1 also shows how state tax revenue is divided among the five categories shown, with ad valorem taxes (mainly on property) being the largest category. For local taxes, ad valorem is also the largest category. Social insurance and state income taxes are the next largest revenue sources, followed by revenue from fees and charges. Business and other taxes make up most of the rest. *

* *

Federal, state and local tax revenues

have changed over time. By far the

greatest increase in total federal

revenue occurred during World War II,

when revenue from the federal income

tax jumped from about 3% to just over

15% of Gross Domestic Product, or GDP

(total value of all goods and

services, currently about $15

trillion). Since then, federal

income tax revenues have ranged from 8

to 12% of GDP. The federal social

program revenues increased greatly

beginning in 1960, usually about 5-6%

of GDP (Chantrill).

State revenues as a percentage of GDP have increased more gradually over time. Ad valorem taxes have stayed more stable over time at the state level while state income taxes and social insurance taxes have increased the most (Chantrill). Local tax revenues showed a big spike relative to GDP in the 1930s (GDP went down to a very low level) and have gradually increased since the early 1940s. Ad valorem taxes have been the largest portion of local revenues. Fees and business taxes have also been also significant parts of local revenues. Business taxes produced relatively smaller parts of totals for federal and state revenues (Chantrill). *

* *

Let's turn to how is the tax money is

being used and what it is used for. As

one joke has it, Congress has the

unsolved problem of how to get the

people to pay taxes they cannot afford

for services they do not need.

How much is wasted? Pork barrel

projects and earmarks come to

mind. Certain members of

Congress from both political parties

have become known as the "Kings of

Pork".

Earmarks are specific amounts of money directed to particular projects. These were estimated to be 1% of the federal budget in 2010, or about $100 per person annually. The process was reformed in 2010 when the U. S. House passed rules that banned earmarks to for-profit corporations. Some, however, say that earmarks are more democratic and less bureaucratic than other appropriations. Foreign aid has sometimes been labeled as wasteful. One wit has said that he wouldn't mind paying income tax if he just knew which country it was going to. In 2012 foreign aid was about $150 per person, or 1.3% of total federal spending and 0.3% of GDP. This $48.4 billion included 17.2 billion for military assistance and 31.3 billion for economic assistance. Afghanistan received the most of this aid in 2012—$12.9 billion, including $9.6 billion in military aid and 3.3 billion in economic aid. Economic aid is used for security support, health and child support, narcotics control, refugee assistance, food aid and development aid. Looking at Table 2, by the numbers, the largest federal spending categories are for health care and pensions.

These are around one

trillion dollars each in FY 2015

($3,125 per person) and together

account for over 50 percent of all

federal spending. The third

largest category is defense, which at

$814 billion ($2,540 per person)

represents 21 percent of total federal

spending. Welfare, at $371

billion ($1,175 per person), and

interest on the debt, at 229 billion

($716 per person), are the next

largest categories.

The total for state level spending is about one and one-half trillion dollars, or nearly $5,000 per person. Health care, at over half a trillion dollars ($1,734 per person), amounts to 36% of state level spending and is the largest amount in the state level column of Table 2. Education, at 284 billion (19%), and pensions, at 236 billion (15%), are the second and third largest state-level spending areas. Welfare and transportation are the next largest categories. The federal transfer payments shown in column 2 of Table 2 are direct payments to individuals for social security, welfare and veterans benefits. Local spending was also estimated at about one and one-half trillion dollars ($4,938 per person). Education was the largest category of local government, accounting for 35% of the total ($1,718 per person). Other categories of local spending include $541 per person for protection (11%), $434 per person for health care (9%), and $434 per person for transportation (9%). *

* *

Have

spending patterns changed over the

years? Charts 1-4 show how

several areas of federal, state and

local government spending have changed

since 1900, as a percentage of

GDP. Total government spending

was approximately 7% of GDP in

1900. It increased to about 20

percent during the Great Depression,

with huge spikes in spending during

the two world wars, mainly due to

increased federal spending (shown in

red).

Chart 1 shows a fairly steady increase in spending in all three levels of government from 1950 to the present, with quite a bit of it at the state (green) and local (gray) levels.  Federal spending has

generally stayed at no more than 20%

of GDP since 1960. Various

bailouts following the mortgage

meltdown of 2008 caused total federal,

state and local spending to reach 41%

of GDP. Future spending is

projected to total about 36%.

Chart 2 shows defense spending spiked to over 20% of GDP during World War I and 41% during World War II. Defense spending then reached 15% of GDP during the Korean War and 10% during the Vietnam War. Current and future spending for defense is projected at about 5.5%.  Spending on education (Chart 3) was 1% of GDP in 1900 and remained below 4% until after 1960.  Education spending did

increase considerably after World War

II, as teacher pay increased, and

reached 6% of GDP in 2008. The

blue area on the Education chart is

for federal grants to state and local

governments.

Health care spending (Chart 4) stayed at or below 1% of GDP until the passage of Medicare and Medicaid legislation in the mid-1960s.  Government spending for

Health Care has increased steadily

from that time, currently standing at

7%. The blue area on the Health

Care chart again represents federal

transfer payment to state and local

governments.

*

* *

Consider the federal budget deficits,

by the numbers. In recent years,

federal spending has run about four

trillion dollars per year with revenue

collections of around 3.5 trillion, so

the annual deficit has run about 0.5

trillion per year. That is 500

billion, or 500 with nine zeros after,

and 500 billion is $1562 for every

person in the country.

That may not sound so terrible for

just one year, but now the total

national debt is up to about

twenty-one trillion dollars or $65,625

per person.

According to Congressional Budget Office (CBO) numbers, federal budget surpluses have occurred in only four of the last forty years. The yearly deficits have been running about 3% of GDP from 1974 through 2013; the 2009 deficit of nearly 10% of GDP was due to the financial crisis and other bailouts. Yearly deficits have been declining from 2010 through 2014, but are projected to again increase between 2015 and 2024 due to the aging of the population, rising health care costs, and interest payments on the federal debt (CBO, "Updated Budget Projections"). The CBO estimates in Chart 5 show total revenues averaged 17.4% of GDP during 1974 through 2013, while total outlays averaged 20.5%.

Chart 5 (CBO website)

Are there ways to

control or eliminate the yearly

deficits or the total debt?

Though it would seem possible to

reduce spending and/or increase

revenues, both have proved extremely

difficult politically.

The budget act of 2011 (known as sequestration) had some success but was uniformly unpopular. Everyone has his or her own special interests and would rather see a cut in someone else's favorite program. Special situations requiring additional spending seem to always come up. The yearly deficits could possibly (or hopefully) be eliminated at some point. Unless that happens for many future years, by these numbers, there is little hope of reducing or eliminating the overall debt. It may be noted by comparing Tables 1 and 2 that state and local revenue and spending are not completely equal. In FY 2015, the states as a group spent less than they taxed while local governments spent 420 billion more than they took in. The estimated public debt is more than a trillion for states and nearly two trillion for local governments. *

* *

Let's

look back at the second assertion

noted at the beginning of the article.

Are some citizens "not paying their

fair share" in taxes? One hears

various statements and claims on this

subject, many implying or stating that

the higher income people ought to pay

more, or that the top 1% of earners

might just as well pay all of the

taxes. These claims tend to be

focused on the federal income taxes,

though we know from Table 1 that

federal income taxes are only about

30% of total federal, state and local

tax revenues.

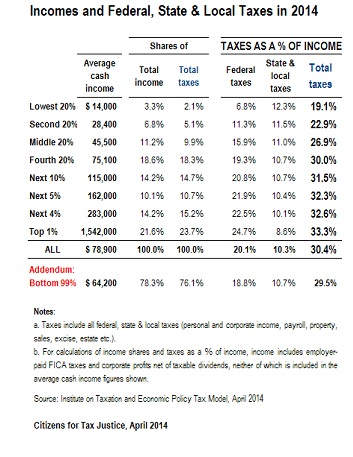

Table 3 compares 2014 average incomes with average amount of all federal, state and local taxes paid by selected groups of taxpayers.

The middle columns of

the table show that, on the average,

the lowest 20 percent of taxpayers

earn 3.3 percent of total income and

pay 2.1 percent of total taxes.

Similarly the middle 20 percent, on

the average, earn 11.2 percent of

total income and pay 9.9 percent of

all taxes. And the top one

percent of earners account for 21.6

percent of total income and pay 23.7

percent of total taxes. Chart 6

shows the total income and total taxes

data graphically.

Chart 6

(from Citizens for Tax Justice

website)

Total

taxes paid by each income group are

fairly similar to their share of

income. So, are all paying

their fair share? By the

numbers, in 2014 each income group

was paying taxes that seem

appropriate for its income

levels.

The

lowest 20% of incomes in the first

line of Table 3 are taxed at 19.1%

overall. It would not be easy to

live on $14,000 per year ($7.00 an

hour) and pay nearly 20% of it on

taxes.

Look at the last three columns of Table 3. These show that federal taxes paid as a percent of income increase as income levels increase—a progressive tax. But the state and local taxes over all states and local areas are slightly regressive—that is, the lower income groups pay a higher percent of their income in taxes and the higher income groups pay somewhat lower percentages. *

* *

Debate over tax policies and fairness

is as old as taxation itself, and it

tends to get loud and

passionate. We will have a

better, more productive debate if we

all first ascertain what the actual

facts of taxation are—by the numbers.

Works

Cited and Consulted

"2015 United

States Federal Budget." Wikipedia. Web.Chantrill, Christopher. Usgovernmentrevenue.com. Web. Citizens for Tax Justice. "Who Pays Taxes in America in 2014?" Web. The Concord Coalition "What Is the Total U. S. National Debt?" Web. Congressional Budget Office. "Overview of the Federal Budget." April 17, 2015. Web. ---. "Updated Budget Projections: 2014 to 2024." April 14, 2014. Web. "Earmark (politics)." Wikipedia. Web. "Earmark Spending." Earmark.org. Web. Edwards, Chris. "Nearly 14,000 Pork Projects In Federal Budget this Year." The Heartlander. Heartland.org. October 1, 2015. Web. Levine, Gary. "Who Really Pays Taxes." levine-cpa.com. April 30, 2012. Web. Messerli, Joe. "List of 100 Taxes & Fees You Pay to the Government." BalancedPolitics.org. Web. Philpott, Tom. "2015 pay pinch to be 2016 pinch if sequester stays." HeraldNet, heraldnet.com, December 17, 2014. Web. "United States foreign aid." Wikipedia. Web. "Who Holds Our Debt?" FactCheck.org. November 19, 2013. Web. Biography

of R. Paul Moore

R.

Paul Moore, a retired statistician,

lives in Syracuse, Nebraska, with his

wife, Judy. They have three

grown children and six

grandchildren.

Paul received a Bachelor of Science degree in Agricultural Economics from the University of Nebraska and a Master of Experimental Statistics degree from North Carolina State University. Paul worked in statistical surveys with the Research Triangle Institute, the United States Department of Agriculture and the United States Census Bureau. His work as statistician, manager, and survey director applied primarily to agriculture, education, health, and transportation problems. He is a charter member of the Southeast Nebraska Torch Club, where he currently serves as President-Elect. This paper was presented at the April 2015 meeting of that club. ©2017 by the International

Association of Torch Clubs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||